Proactive Complementarity (Revisited)

The single most powerful tool available to the ICC to catalyze such territorial prosecutions remains the threat of ICC prosecution. […] In short, most states do not want the ICC to step in and supplant their own domestic judicial processes. So they may become more willing to undertake prosecutions themselves in the face of a pending international prosecution. […] The ICC has a proven (albeit imperfect) track record of indictments, arrests, and prosecutions. That track-record is now a form of political capital that the ICC can rely upon to show national governments that when the Court decides to prosecute, it will actually do so.

Summary

Fifteen years ago, I argued that the International Criminal Court (ICC) should implement a strategy of “proactive complementarity” or, as some have called it, “positive complementarity.”1 Under this model, the ICC would take an active approach in encouraging and supporting domestic prosecutions of international crimes, particularly in the state in which those crimes occurred. A significant consideration in my argument was that the mere threat of prosecution by an international tribunal could incentivize territorial states to prosecute such crimes so as to avoid international intervention and supervision. Initial evidence, from cases including Bosnia (where the ICTY was actively undertaking prosecutions) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (where the ICC was active) supported this pathway to domestic accountability.2

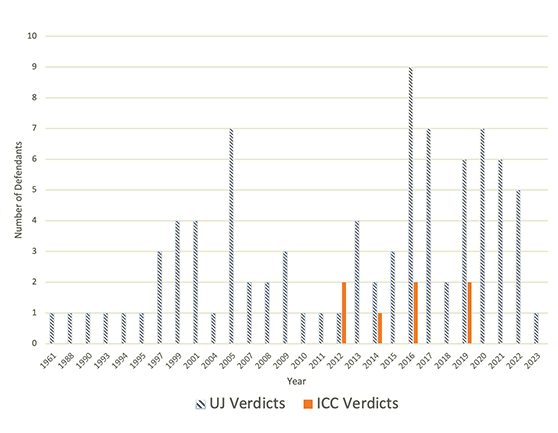

When I put those arguments forward, the ICC was still a brand-new institution, building its capacities and opening its first investigations. Attention was focused far more on how the ICC might get cases and apprehend suspects than it was on how the ICC might get rid of cases and send suspects back to national jurisdictions. Fifteen years later, the question has flipped. With seventeen situations under investigation and more than fifty individuals indicted,3 it has become clear that the ICC—no matter how efficient or well-resourced it becomes—cannot prosecute all the cases currently before it, much less the full range of serious international crimes occurring in the world today. Some have described it as a “capacity crisis” that “threatens not only the ICC’s effectiveness, but also its legitimacy.”4

While the case overload at the ICC is problematic, the broader structural considerations that limit the Court’s capacity are not. In fact, those structural limitations should be embraced. During the negotiation of the Rome Statute in 1998, the ICC was conceived of as a Court of limited jurisdiction, secondary to national courts. After all, the Preamble to the Rome Statute makes clear that it is the duty of states “to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes” and that the Court is “complementary to national criminal jurisdictions.”5

While the young ICC—particularly under its first two prosecutors—focused on building its own capacities, it was reluctant to actively engage with national jurisdictions to encourage their own prosecutions of international crimes. ICC officials did, of course, take part in consultations and trainings in some states in which it was undertaking investigations. But it did not make it an institutional priority to systematically advance and support national prosecutions of international crimes, especially those under active ICC investigation. The time has come for it to do so. In fact, today’s more mature ICC has far more capacity and influence to actually catalyze national prosecutions than it did back in 2005.

Argument

I. The ICC’s Ability to Catalyze National Prosecutions

Generally speaking, domestic prosecutions of international crimes fail for two key reasons: lack of political will and lack of capacity.6 The ICC has the ability to assist states in overcoming both of these limitations. The Rome Statute specifically authorizes and envisions the Court to play a role in moving domestic prosecutions forward. Article 93(10)(a) provides:

The Court may, upon request, cooperate with and provide assistance to a State Party conducting an investigation into or trial in respect of conduct which constitutes a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court or which constitutes a serious crime under the national law of the requesting state.7

The modalities of that assistance, however, will differ with respect to domestic prosecutions undertaken by the territorial state and those that would be based on universal jurisdiction. In both scenarios, however, there is much the ICC can and should do to advance domestic efforts at accountability. There are also limits to what the Court can and should offer states that must inform its efforts.

A. Territorial Prosecutions

Given that it remains the primary international legal duty of territorial states to prevent and punish the most serious crimes in international law and that there are recognized benefits from locating prosecutions as close to the events and victims as possible, the ICC’s priority should be to incentivize the state in which the relevant crimes occurred to prosecute.8 The single most powerful tool available to the ICC to catalyze such territorial prosecutions remains the threat of ICC prosecution. As I argued back in 2005:

[ICC] intervention into otherwise exclusively domestic criminal processes imposes considerable sovereignty costs on national governments that states may seek to avoid by undertaking their own investigations and prosecutions.9

In short, most states do not want the ICC to step in and supplant their own domestic judicial processes. So they may become more willing to undertake prosecutions themselves in the face of a pending international prosecution.

In 2005, it was understandable that many states might be skeptical of whether the ICC would, in fact, open an investigation of events on their territories, much less actually prosecute the perpetrators of such crimes. At the time, the Court’s track record was limited and many of its early high-profile indictees—such as Joseph Kony and Omar al-Bashir—were still at large. Eighteen years later, however, the ICC has a proven (albeit imperfect) track record of indictments, arrests, and prosecutions. That track-record is now a form of political capital that the ICC can rely upon to show national governments that when the Court decides to prosecute, it will actually do so. The near certainty of the ICC following through on its commitments to exercise jurisdiction will be sufficient to motivate at least some states to prosecute domestically.

When seeking to catalyze prosecutions by territorial states, the ICC’s leverage vis-à-vis a national government increases the closer the ICC is to undertaking its own prosecution. In some cases, naming a country as part of a situation under investigation may be sufficient. The actual indictment of specific individuals generates even more leverage to encourage domestic judicial action. Apprehension of a suspect subject to potential transfer to the Hague likely generates the most international pressure for a country to investigate and prosecute a particular individual. This phenomenon has proved true in Kosovo (with respect to potential ICTY prosecution) and led to the establishment of the Kosovo Specialist Chambers.10 In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, similar external pressure by the ICC and a subsequent judicial reform led to the prosecution of some military leaders in Congolese courts.11

More recently, the ICC’s long and difficult negotiations with the government of Sudan over the transfer or trial of Omar al-Bashir is indicative of both the influence it may have with national governments and the limits thereof. The closer the ICC came to actually being able to arrest Bashir, the more willing the Sudanese government became to consider domestic prosecution as an alternative. As Sudan’s Justice minister explained in 2000:

[O]ne possibility is that the ICC will come here so they will be appearing before the ICC in Khartoum, or there will be a hybrid court maybe, or maybe they are going to transfer them to The Hague. That will be discussed with the ICC.12

The ICC should use exactly this sort of pressure to nudge territorial states toward domestic prosecutions.

Where, in light of an ICC indictment, a territorial state becomes open to undertaking a genuine domestic investigation, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) should use that indictment as leverage both for the arrest of the suspect and transfer to the Hague and for the initiation of a domestic prosecution. Even where the ICC has already issued an indictment or apprehended a suspect, its legal obligation is, and policy goal should be, to prioritize domestic prosecution rather than exercise jurisdiction itself. Ultimately, such a warrant must be understood as a step toward accountability—international or domestic—and not as an indication that a case is now exclusively within the ICC’s jurisdiction. Articles 18 and 19 of the Rome Statute allow admissibility to be challenged throughout procedural phases at the ICC. Where a national government begins its own prosecution, the ICC must defer.

So too, the ICC must be open to the reality that such domestic prosecutions may take different forms and may not follow ICC rules and procedures. In some cases, a territorial state may be willing to establish a semi-internationalized special tribunal; in others they may demand a purely domestic trial based on its own national approaches to justice. For a model of proactive complementarity to be viable, the ICC, as well as the international justice community, will need to become more comfortable with variation in the procedures and processes of accountability.13 That is precisely why the Rome Statute’s admissibility requirements define acceptable domestic prosecutions broadly under the rubric of genuineness.

Political pressure to change a state’s willingness to undertake the prosecution of international crimes is only one piece of the puzzle. In addition, territorial states undertaking such prosecutions may need a range of other assistance, including expertise, evidence, resources, and perhaps even the handover of the accused. Each of these forms of assistance are at least theoretically plausible under Article 93 of the Statute. Nonetheless, the ICC is not, and should not become, a judicial development organization—that is not part of its mandate nor its expertise.14 Hence, the ICC must be judicious in its efforts to support—as opposed to incentivize—national prosecutions.

Expertise is by far the easiest and most appropriate form of support the ICC can offer to territorial states undertaking prosecutions of international crimes. Such expertise can come in many forms ranging from training sessions to the short-term secondment of ICC personnel. Where countries are genuine in their efforts to undertake domestic prosecutions, and willing to learn from the Court’s expertise, the ICC should actively prioritize such efforts and build them into the mission and budget of the OTP. Regular secondments of ICC personnel to countries that are engaged in investigations and prosecutions should become routine.

The ICC’s provision of evidence to a national government elevates the stakes of its involvement in a domestic prosecution and raises potential pitfalls. Any provision of evidence under Article 93 of the Statute should be predicated on concrete steps by the national government that demonstrate its commitment to a genuine prosecution. Such evidentiary support should be based on a written agreement with the government as to how that evidence will be used and protected. Some forms of evidence may be easy to provide to national governments, particularly where they reflect the ICC’s compilation of open-source data and information. In contrast, other forms of evidence—that may implicate victims, reveal witness information, or compromise sources and methods of evidence collection—may simply be inappropriate for handover to national government.15 In such circumstances, the national government may build parts of its case without ICC support.

Generally speaking, the ICC is not a donor organization and should not provide direct transfers of financial resources to national governments. The Court’s own resources are limited and the Assembly of States’ Parties has not made financial transfers a priority within the Court’s budget. Countries seeking to undertake domestic prosecutions of international crimes will need to look to other funding sources, including their own national budgets, bilateral development aid, and philanthropic support to fund their efforts.16 That said, the ICC may be able to encourage such financial support through the signals it sends to the donor community by training national judicial officials, seconding personnel, or reaching an agreement on the provision of evidence.

Perhaps the most important—but also the most potentially problematic—step the ICC could take to support a domestic prosecution would be the transfer of an indictee from the Court to the national jurisdiction. Ultimately, such transfers may be necessary to address the ICC’s current case backlog and are a necessary element of prioritizing domestic prosecutions. But the hand-back of indictees should only occur where a national government has been determined by the Pre-Trial Chamber to satisfy the complementarity requirements under Article 17 of the Statute and the Court has appropriate assurances as to the genuineness and fairness of the national prosecutions that will result. Such a step should not be undertaken lightly, but it must be understood not as a failure of the ICC, but as the successful realization of the goals of the Rome Statute.17

Of course, in any case in which the ICC considers deferring to national prosecutions, and particularly in cases in which it might hand an indictee back to a territorial state, it will need to remain vigilant that prosecutions are in fact genuine. So too, the Court will need to ensure that a minimum level of human rights protections are in place and that a trial is fair. To that end, the OTP should negotiate and memorialize an agreement with a national government prior to the handover of an indictee, ensuring the genuineness of a subsequent prosecution. The resulting trial may not be procedurally identical to an ICC prosecution, but it will still advance the goal of ending impunity while relieving the Court of some of its judicial burden. The time has come to recognize that imperfect justice—at least according to international standards—may be better than justice delayed, as long as basic human rights are respected.

B. Prosecutions Under the Principle of Universal Jurisdiction

The ICC may also have a role to play in assisting national courts undertaking prosecution of international crimes under the principle of universal jurisdiction. While universal jurisdiction has existed with respect to international crimes for centuries, there appears to be a growing willingness among at least some national governments to undertake such prosecutions.18 Universal jurisdiction prosecutions must be understood as an integral part of the overall Rome system of justice and an important piece of the broader effort to end impunity. While the ICC can not and should not be expected to coordinate a mosaic of domestic courts prosecuting international crimes, it can incentivize and support such prosecutions.19 It could also serve as an information and expertise hub in a decentralized system of domestic justice for international crimes.20

The logic behind the ICC’s ability to catalyze non-territorial states to prosecute international crimes under universal jurisdiction differs from the ways it can influence territorial states to prosecute crimes domestically. Third states exercising universal jurisdiction do not fear the sovereignty costs of international intervention. In fact, the threat of ICC prosecution might actually give third states reason not to prosecute themselves. After all, the prosecution of international crimes is often expensive and may divert resources from a country’s domestic justice system. Third states might well prefer to defer to the ICC if it is willing to prosecute. Hence, when working with states considering exercising universal jurisdiction, the ICC must emphasize not the threat of ICC prosecution, but rather its own limited capacity, the dangers of impunity, and the need for action by national governments.

Most states considering the exercise of universal jurisdiction are committed to the broader goal of ending impunity. Some may have a historical or other ties to the perpetrator or territorial state where the crime occurred, giving them particular incentive to ensure justice is realized.21 Rather than sending such states a signal that the ICC will undertake prosecutions itself, the Court should make clear to third states that its own capacity is limited, that it remains the primary obligation of national governments to end impunity, and that if a prosecution is not undertaken based on universal jurisdiction, the perpetrator may well avoid accountability. Appropriately calibrated diplomatic messaging can and should be part of the work of the OTP, encouraging universal jurisdiction prosecutions whenever possible.

Beyond political pressure and diplomatic messaging, the ICC may also be able to provide evidentiary and technical assistance to national governments exercising universal jurisdiction. The same broad objectives and considerations discussed above with respect to territorial prosecutions will apply in this context as well. The Court can and should provide technical assistance and expertise when needed. It may consider evidence sharing, if appropriate safeguards are in place. Finally, in appropriate circumstances and with written assurances about the terms and procedures of a universal jurisdiction prosecution, it may consider handing over already apprehended suspects for domestic prosecution. It should not, however, finance domestic prosecutions—whether territorial or based on universal jurisdiction.

The Court’s involvement in cases brought under universal jurisdiction may present fewer concerns than its support for territorial states undertaking domestic prosecutions. Generally speaking, the interests and objectives of countries exercising universal jurisdiction will be more clear-cut and hopefully aligned with the goals of the Rome Statute. Such countries are also likely to have more developed domestic judiciaries and require less assistance from ICC. The sharing of evidence may be facilitated by the existence of adequate legal protection of both evidence and witnesses under the requesting state’s domestic judicial system. Where the ICC is able to share evidence, it may reduce the burdens on the prosecuting state, perhaps allowing that state to prosecute where it would not have had the resources to do so without ICC support.

Nonetheless, the ICC must remain vigilant when cooperating even with states exercising universal jurisdiction. There may well be states seeking to exercise universal jurisdiction that have mixed motives for prosecuting, or other states that seek to exercise universal jurisdiction, but lack adequate domestic legal frameworks to protect evidence or the rights of victims or the accused. In such circumstances, the ICC should play a more limited role (perhaps offering trainings and expertise) or no role at all. The Court may wish to remind states diplomatically that, where a case under universal jurisdiction fails to meet the tests of genuineness, the ICC may decide to act on its own.

Beyond active support for domestic prosecutions under universal jurisdiction, the ICC can easily position itself as a hub in a broader system of justice for the most serious international crimes. At the very least, the ICC can serve as a repository of information on the prosecution of crimes within its jurisdiction undertaken by states based on universal jurisdiction. Cataloguing and sharing such information would allow the Court to show the broader movement toward ending impunity and perhaps highlight for governments the potential of universal jurisdiction to contribute to those efforts.

II. The Limits of Positive Complementarity

This comment has focused on how the ICC can do more to catalyze domestic prosecutions of international crimes, either by territorial states or by states exercising universal jurisdiction. While the time is right for the Court to make such efforts a central part of its mission and, thereby, relieve some of its caseload, there are limits both to what the Court can do to incentivize such prosecutions and what it is appropriate for national governments to do in undertaking such prosecutions. Those limitations on domestic justice is precisely why the ICC was established in the first place: to prosecute the most serious crimes when national governments are unable or unwilling to do so. There are a variety of circumstances in which the Court should not pursue a strategy of proactive complementarity.

A. Where Domestic Prosecutorial Efforts Lack Genuineness

Any efforts to catalyze domestic prosecutions of international crimes must be predicated on the willingness of states to undertake genuine prosecutions. The genuineness requirement is enshrined in Article 17 of the Rome Statute and is essential for ensuring rights, justice, and accountability. As outlined in this comment, the ICC can and should push states toward meeting those requirements. Initially, the Court may need to accept the good faith of such governments, until their actions call such good faith into question.22 Where genuineness is in doubt, the Court may be advised to take only small steps to assist states with domestic prosecutions, while carefully monitoring the actions and motivations of the national government interested in prosecuting the case. When and if it becomes clear that a government does not intend to undertake a genuine prosecution, the ICC must cease its efforts to catalyze that government forward. In such cases, the Court may decide to prosecute itself, may seek to encourage third states to act under universal jurisdiction, or may simply have to recognize that, given resource limitations, accountability may not be presently feasible.

B. Where Crimes Fall Outside the ICC’s Jurisdiction or Gravity Thresholds Are Not Met

The ICC must remain focused on the most serious crimes that fall within its jurisdiction. There are a range of crimes subject to universal jurisdiction, but that are not within the Court’s jurisdiction. Some crimes (such as piracy) may be subject to universal jurisdiction, but not included expressly in the Rome Statute. Similarly, national governments may seek assistance with the prosecution of crimes that do not meet the nationality or territoriality requirements for ICC prosecution. The ICC should not actively assist such prosecutions given its limited mandate and resources.

Even with respect to crimes within the Court’s jurisdiction (such as Crimes Against Humanity), there may be circumstances in which national governments prosecute crimes under universal jurisdiction that do not meet the ICC’s gravity thresholds.23 While such prosecutions should be lauded as part of the broader effort of ending impunity, the ICC should not prioritize assisting national governments with such prosecutions. Again, the ICC is not a judicial development or capacity-building mechanism.24 Of course, the ICC’s assistance to states exercising universal jurisdiction over crimes within the Court’s jurisdiction, and that satisfy its gravity threshold, may have knock-on effects of enhancing that country’s domestic justice capability. Such side effects should be viewed positively, but not prioritized.

C. Where Crimes Involve the Prosecution of Sitting Government Officials With Immunity Before Domestic Courts

The drafters of the Rome Statute recognized the need to hold even sitting senior government officials accountable for international crimes. To that end, they gave the Court the power to prosecute such officials even while they remain in office by providing that official capacity would be irrelevant before the ICC.25 In contrast, national courts can not prosecute senior sitting government officials under universal jurisdiction.26 The ICC should not endeavor to support such prosecutions domestically, but instead should seek to exercise jurisdiction itself.

D. Where a Prosecution Has High Symbolic Value or Poses Systemic Risks

Some cases present unique political challenges for the prosecuting state or the international community as a whole. While all prosecutions of international crimes are complex, and most are politically charged in the state in which the crimes occurred, certain cases may pose a greater degree of political risk. The 2023 indictment of sitting Russian president Vladimir Putin is a prime example. As President of Russia, Putin is, of course, immune from prosecution in the domestic courts of any third state. However, if he were to leave office—or be forced out of office—a domestic prosecution could be plausible. The ICC should not attempt to catalyze or support such a prosecution. The prosecution of Putin in Ukraine or in any G7 member country would run the risk of being seen as victor’s justice or it could exacerbate or rekindle military conflict. Similarly, in some post conflict states, a domestic prosecution might destabilize a fragile peace agreement or prompt a new wave of violence and retribution.27 Once again, these are circumstances in which the ICC should undertake its own prosecutorial efforts rather than encourage domestic prosecutions.

III. Conclusion

The ICC has made great progress in the past twenty-three years. But, its success also highlights its limitations. The Court presently has before it more cases and suspects than it can reasonably handle. Unfortunately, events the world over continue to expand its docket. The solution to the ICC’s capacity challenge is actually found in its Statute—that the Court can and should encourage and support the domestic prosecutions of international crimes. By catalyzing and, at times, supporting national prosecutions both by territorial states and by sates acting under universal jurisdiction, the ICC can maximize its ability to end impunity while slimming its own caseload. Caution must be exercised in the process and new techniques and tools will need to be developed by the Court. Ultimately, more active efforts to catalyze domestic prosecutions may contribute to ending impunity more broadly than just through its own prosecutions.

Endnotes — (click the footnote reference number, or ↩ symbol, to return to location in text).

-

1.

Proactive Complementarity: The International Criminal Court and National Courts in the Rome System of Justice, 49 Harv. Int’l L.J. 53 (Dec. 2008), paywall. ↩

-

2.

The Domestic Influence of International Criminal Tribunals: The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the Creation of the State Court of Bosnia & Herzegovina, 46 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 279 (2008), available online; Complementarity in Practice: the International Criminal Court as Part of a System of Multi-Level Global Governance in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 18 Leiden J. Int’l L. 557 (Oct. 2005), paywall, doi. ↩

-

3.

Defendants, ICC, available online (last visited Aug. 27, 2023). ↩

-

4.

& , The International Criminal Court at Risk, Open Democracy (May 6, 2015), available online. ↩

-

5.

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Adopted by the United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court, Jul. 17, 1998, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.183/9, as amended [hereinafter Rome Statute], Preamble, available online. ↩

- 6.

- 7.

-

8.

Id. Preamble; , U.N. Doc. A/Res/60/1, 2005 World Summit Outcome, ¶ 138 (Sep. 16, 2005), available online; The Future of International Criminal Justice, 4 HJJ 257 (2009), available online. ↩

- 9.

-

10.

, The Specialist Chambers of Kosovo: The Limits of Internationalization, 14 J. Int’l Crim. Just. 25 (Mar. 15, 2016), paywall, doi. ↩

-

11.

Accountability for Atrocities Committed in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Supporting the Governments Proposal to Establish Specialized Mixed Chambers and Other Related Judicial Reforms (Apr. 1, 2014), available online. ↩

-

12.

, The ICC Inches Closer to Bashir as Sudan and Israel Normalize Relations, Just. in Conflict (Oct. 28, 2020), available online; Omar Bashir: ICC Delegation Begins Talks in Sudan Over Former Leader, BBC News, Oct. 17, 2020, available online. ↩

-

13.

, The Pluralism of International Criminal Law, 86 Ind. L.J. 1063 (Jul. 2011), available online; , The Pace of International Criminal Justice, 31 Mich. J. Int’l L. 79 (Nov. 2009), available online. ↩

-

14.

, Justice on the Ground: Can International Criminal Courts Strengthen Domestic Rule of Law in Post-Conflict Societies?, 1 HJRL 87–97 (2009), available online, doi; , & , Complementarity After Kampala: Capacity Building and the ICC’s Legal Tools, 2 GoJIL 791 (2010), available online, doi. ↩

-

15.

, Witness Protection Measures at the International Criminal Court: Legal Framework and Emerging Practice, 23 Crim. L. Forum 97 (Jul. 25, 2012), available online, doi. ↩

-

16.

Towards a New Consensus on Access to Justice: Summary of Brussels Workshop (2008), available online. ↩

-

17.

Rome Statute, supra note 5, Preamble. ↩

-

18.

Universal Jurisdiction Annual Review 2020 (Mar. 18, 2020), available online. ↩

-

19.

, Will the ICC have an Impact on Universal Jurisdiction?, 1 J. Int’l Crim. Just. 585 (Dec. 1, 2003), paywall, doi. ↩

-

20.

A Community of Courts: Toward a System of International Criminal Law Enforcement, 24 Mich. J. Int’l L. 1 (2002), available online. ↩

-

21.

& , Criminal Justice is Local: Why States Disregard Universal Jurisdiction for Human Rights Abuses, 55 Vand. J. Transnat’l L. 375 (Jun. 2022), available online. ↩

-

22.

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, art. 26, May 23, 1969, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331, available online, archived. ↩

-

23.

Rome Statute, supra note 5, Article 17(1)(d); , The Meaning of Gravity at the International Criminal Court: A Survey of Attitudes About the Seriousness of Mass Atrocities, 24 U.C. Davis J. Int’l L. & Pol’y 209 (2018), available online. ↩

-

24.

Rome Statute, supra note 5, Preamble. ↩

- 25.

-

26.

Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of Congo v. Belgium), Judgment, 2002 I.C.J. Rep. 3 (Feb. 14, 2002), available online, archived; ↩

-

27.

& , Conflict Recurrence and Post Conflict Justice: Addressing Motivations and Opportunities for Sustainable Peace, 61 Int’l Stud. Q. 690 (Sep. 2017), available online, doi. ↩

-

Suggested Citation for this Comment:

, Proactive Complementarity (Revisited), ICC Forum (Sep. 13, 2023), available at https://iccforum.com/decentralized-accountability#Burke-White.

Suggested Citation for this Issue Generally:

How Should the ICC Support Decentralized Accountability for Those Accused of Grave Crimes?, ICC Forum (Sep. 13, 2023), available at https://iccforum.com/decentralized-accountability.